QUOTE

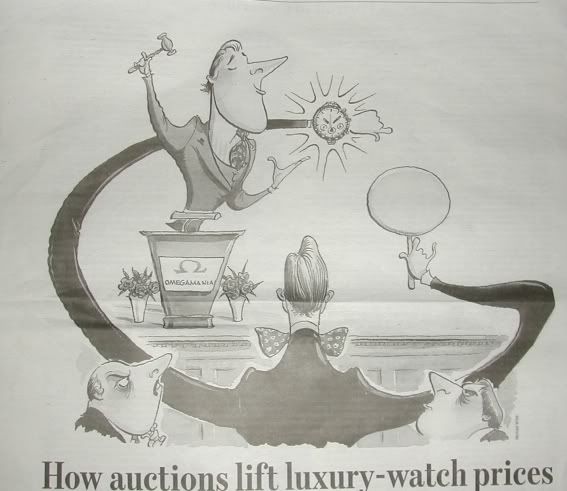

GENEVA -- In the rarefied world of watch collecting, where Wall Street investment bankers and Asian millionaires buy and sell at auctions, a timepiece can command a higher price than a luxury car. At an April event here, a 1950s Omega platinum watch sold for $351,000, a price that conferred a new peak of prestige on a brand known for mass-produced timepieces.

Watch magazines and retailers hailed the sale, at an auction in the lush Mandarin Oriental Hotel on the River Rhone. Omega trumpeted it, announcing that a "Swiss bidder" had offered "the highest price ever paid for an Omega watch at auction."

What Omega did not say: The buyer was Omega itself.

Antiquorum sometimes stages auctions for a single brand, joining with the watchmakers to organize them, in events at which the makers often bid anonymously. This is a technique of which Patek Philippe and other famous brands, as well, have availed themselves.

"It's an entirely different approach to promoting a brand," says the cofounder of Antiquorum, Osvaldo Patrizzi, "Auctions are much stronger than advertising." Mr. Patrizzi worked with Omega executives for two years on the auction, publishing a 600-page glossy catalog and throwing a fancy party in Los Angeles to promote the event. "We are collaborators," he says.

But now there's ferment in the world of watch auctions. First, they're starting to raise ethical questions, even within the industry. "A lot of the public doesn't know that the biggest records have been made by the companies themselves," says Georges-Henri Meylan, chief executive of Audemars Piguet SA, a high-end Swiss watchmaker. "It's a bit dangerous."

More unsettling, Antiquorum's Mr. Patrizzi, who essentially founded the business of watch auctions, is under fire by the house he cofounded. Its board ousted Mr. Patrizzi as chairman and chief executive two months ago -- and hired auditors to scour the books.

The business of auctions for collectibles is not a model of transparency. The identities of most bidders are known only to the auction houses. Sellers commonly have a "reserve," or minimum, price, and when the bidding is below that, the auctioneer often will bid anonymously on the seller's behalf. However, the most established houses, such as Christie's International PLC, announce when the seller of an item keeps bidding on it after the reserve price has been reached.

Omega's president, Stephen Urquhart, says the company is not hiding the fact that Omega anonymously bid and bought at an auction. He says Omega bought the watches so it could put them in its museum in Bienne, Switzerland. "We didn't bid for the watches just to bid. We bid because we really wanted them," he says. Omega's parent, Swatch Group Ltd., declined to comment.

Through the auctions, Swiss watchmakers have found a solution to a challenge shared by makers of luxury products from jewelry to fashion: getting their wares perceived as things of extraordinary value, worth an out-of-the-ordinary price. When an Omega watch can be sold decades later for more than its original price, shoppers for new ones will be readier to pay up. "If you can get a really good auction price, it gives the illusion that this might be a good buy," says Al Armstrong, a watch and jewelry retailer in Hartford, Conn.

Niche watchmakers have used the auction market for years to raise their profiles and prices, mainly among collectors. As mainstream brands like Omega embrace auctions, increasing numbers of consumers are affected by the higher prices.

Omega and Antiquorum got together at the end of 2004. The watchmaker was struggling to restore its cachet. Omega once equaled Rolex as a brand with appeal to both collectors and consumers, but in the 1980s, Omega sought to compete with cheap Asian-made electronic quartz watches by making quartz timepieces itself. Omega closed most of its production of the fine mechanical watches for which Switzerland was famed, tarnishing its image.

A decade later, Omega tried to revive its luster by reintroducing high-end mechanical models. It raised prices and signed on model Cindy Crawford and Formula 1 driver Michael Schumacher for ads. When this gambit failed to lure the biggest spenders, Omega turned to a man who could help.

Mr. Patrizzi, 62 years old, had gone to work at a watch-repair shop in Milan at 13 after the death of his father, dropping out of school. He later moved to the watchmaking center of Geneva, at first peddling vintage timepieces from stands near watch museums.

He founded Antiquorum, originally called Galerie d'Horlogerie Ancienne, in the early 1970s with a partner. At the time, auctions of used watches were rare, in part because it was hard to authenticate them. But Mr. Patrizzi knew how to examine the watches' intricate movements and identify whether they were genuine.

At first, prominent watchmakers were wary. Mr. Patrizzi approached Philippe Stern, whose family owns one of the most illustrious brands, Patek Philippe, and proposed a "thematic auction" featuring only Pateks. The pitch: Patek would participate as a seller, helping drum up interest, and also as a buyer. A strong result would allow Patek to market its wares not just as fine watches but as auction-grade works of art.

The first Patek auction in 1989 featured 301 old and new watches, with Mr. Patrizzi's assessments, and fetched $15 million. Mr. Stern became a top Patrizzi client, buying hundreds of Patek watches at Antiquorum auctions, sometimes at record prices. The brand's retail prices soared. Over the next decade, the company began charging about $10,000 for relatively simple models and more than $500,000 for limited-edition pieces with elaborate functions known in the watch world as "complications."

Patek began promoting its watches as long-term investments. "You never actually own a Patek Philippe," ads read. "You merely look after it for the next generation." Mr. Stern says he bid on used Patek watches as part of a plan to open a company museum in 2001. Building that collection, he says, was key to preserving and promoting the watchmaker's heritage, the brand's most valuable asset with consumers. "Certainly, through our action, we have been raising prices," he says.

Auctions gradually became recognized as marketing tools. Brands ranging from mass-producers like Rolex and Omega to limited-production names like Audemars Piguet and Gerald Genta flocked to the auction market with Antiquorum and other houses. Cartier and Vacheron Constantin, both owned by the Cie. Financière Richemont SA luxury-goods group in Geneva, have starred in separate single-brand auctions organized by Mr. Patrizzi.

"Patek opened a lot of doors for us, but we also opened a lot of doors for Patek," he says.

Watch magazines and retailers hailed the sale, at an auction in the lush Mandarin Oriental Hotel on the River Rhone. Omega trumpeted it, announcing that a "Swiss bidder" had offered "the highest price ever paid for an Omega watch at auction."

What Omega did not say: The buyer was Omega itself.

Antiquorum sometimes stages auctions for a single brand, joining with the watchmakers to organize them, in events at which the makers often bid anonymously. This is a technique of which Patek Philippe and other famous brands, as well, have availed themselves.

"It's an entirely different approach to promoting a brand," says the cofounder of Antiquorum, Osvaldo Patrizzi, "Auctions are much stronger than advertising." Mr. Patrizzi worked with Omega executives for two years on the auction, publishing a 600-page glossy catalog and throwing a fancy party in Los Angeles to promote the event. "We are collaborators," he says.

But now there's ferment in the world of watch auctions. First, they're starting to raise ethical questions, even within the industry. "A lot of the public doesn't know that the biggest records have been made by the companies themselves," says Georges-Henri Meylan, chief executive of Audemars Piguet SA, a high-end Swiss watchmaker. "It's a bit dangerous."

More unsettling, Antiquorum's Mr. Patrizzi, who essentially founded the business of watch auctions, is under fire by the house he cofounded. Its board ousted Mr. Patrizzi as chairman and chief executive two months ago -- and hired auditors to scour the books.

The business of auctions for collectibles is not a model of transparency. The identities of most bidders are known only to the auction houses. Sellers commonly have a "reserve," or minimum, price, and when the bidding is below that, the auctioneer often will bid anonymously on the seller's behalf. However, the most established houses, such as Christie's International PLC, announce when the seller of an item keeps bidding on it after the reserve price has been reached.

Omega's president, Stephen Urquhart, says the company is not hiding the fact that Omega anonymously bid and bought at an auction. He says Omega bought the watches so it could put them in its museum in Bienne, Switzerland. "We didn't bid for the watches just to bid. We bid because we really wanted them," he says. Omega's parent, Swatch Group Ltd., declined to comment.

Through the auctions, Swiss watchmakers have found a solution to a challenge shared by makers of luxury products from jewelry to fashion: getting their wares perceived as things of extraordinary value, worth an out-of-the-ordinary price. When an Omega watch can be sold decades later for more than its original price, shoppers for new ones will be readier to pay up. "If you can get a really good auction price, it gives the illusion that this might be a good buy," says Al Armstrong, a watch and jewelry retailer in Hartford, Conn.

Niche watchmakers have used the auction market for years to raise their profiles and prices, mainly among collectors. As mainstream brands like Omega embrace auctions, increasing numbers of consumers are affected by the higher prices.

Omega and Antiquorum got together at the end of 2004. The watchmaker was struggling to restore its cachet. Omega once equaled Rolex as a brand with appeal to both collectors and consumers, but in the 1980s, Omega sought to compete with cheap Asian-made electronic quartz watches by making quartz timepieces itself. Omega closed most of its production of the fine mechanical watches for which Switzerland was famed, tarnishing its image.

A decade later, Omega tried to revive its luster by reintroducing high-end mechanical models. It raised prices and signed on model Cindy Crawford and Formula 1 driver Michael Schumacher for ads. When this gambit failed to lure the biggest spenders, Omega turned to a man who could help.

Mr. Patrizzi, 62 years old, had gone to work at a watch-repair shop in Milan at 13 after the death of his father, dropping out of school. He later moved to the watchmaking center of Geneva, at first peddling vintage timepieces from stands near watch museums.

He founded Antiquorum, originally called Galerie d'Horlogerie Ancienne, in the early 1970s with a partner. At the time, auctions of used watches were rare, in part because it was hard to authenticate them. But Mr. Patrizzi knew how to examine the watches' intricate movements and identify whether they were genuine.

At first, prominent watchmakers were wary. Mr. Patrizzi approached Philippe Stern, whose family owns one of the most illustrious brands, Patek Philippe, and proposed a "thematic auction" featuring only Pateks. The pitch: Patek would participate as a seller, helping drum up interest, and also as a buyer. A strong result would allow Patek to market its wares not just as fine watches but as auction-grade works of art.

The first Patek auction in 1989 featured 301 old and new watches, with Mr. Patrizzi's assessments, and fetched $15 million. Mr. Stern became a top Patrizzi client, buying hundreds of Patek watches at Antiquorum auctions, sometimes at record prices. The brand's retail prices soared. Over the next decade, the company began charging about $10,000 for relatively simple models and more than $500,000 for limited-edition pieces with elaborate functions known in the watch world as "complications."

Patek began promoting its watches as long-term investments. "You never actually own a Patek Philippe," ads read. "You merely look after it for the next generation." Mr. Stern says he bid on used Patek watches as part of a plan to open a company museum in 2001. Building that collection, he says, was key to preserving and promoting the watchmaker's heritage, the brand's most valuable asset with consumers. "Certainly, through our action, we have been raising prices," he says.

Auctions gradually became recognized as marketing tools. Brands ranging from mass-producers like Rolex and Omega to limited-production names like Audemars Piguet and Gerald Genta flocked to the auction market with Antiquorum and other houses. Cartier and Vacheron Constantin, both owned by the Cie. Financière Richemont SA luxury-goods group in Geneva, have starred in separate single-brand auctions organized by Mr. Patrizzi.

"Patek opened a lot of doors for us, but we also opened a lot of doors for Patek," he says.

More at http://thewatchery.blogspot.com/2007/10/invisible-hand.html

I never knew that patek phillippe, Audemars Piguet and Omega are involved in outbidding and buying their own watches at record prices in auction houses to create brand awareness and increase its own prestige.

Dubious and almost outright unethical, nevertheless clever.

May 26 2010, 06:43 PM

May 26 2010, 06:43 PM

Quote

Quote

0.9230sec

0.9230sec

0.60

0.60

6 queries

6 queries

GZIP Disabled

GZIP Disabled