The Empire and the Early ChurchA Tale of Persecution—and Justice

By: Christopher Check They refuse to obey an imperial edict to burn incense before the idols of the ancient Roman gods. They are 40 legionaries serving on the Armenian frontier and they are Christians. Christianity recently had been declared legal by Constantine, but his authority is in the west. His counterpart in the east is Licinius, who is resentful of Constantine’s growing power and of his growing interest in Christianity. Licinius ignores the lessons learned by emperors, governors, and prefects of Rome’s past three centuries: Persecution has only increased the resolve and numbers of this troublesome sect. He ignores the words of Tertullian that the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the faith.

The local magistrate warns the soldiers of the disgrace that will befall them should they not offer the sacrifice. He offers promotion to any that will. Yet “no threat or bribe will induce them to forsake Jesus Christ” (Giuseppe Riciotti, The Age of Martyrs: Christianity from Diocletian to Constantine, 212).

Bound with one chain and confined to a small cell, they write a letter exhorting their fellow Christians to leave aside the things of this world and to fix their hearts on heaven. Knowing they are to be martyred, they urge their fellow Christians not to quarrel over their relics.

After weeks in jail, they are sentenced: They are to be stripped of their clothes, marched to the middle of a frozen lake, and exposed to the cold and wind of the Armenian winter until they are dead. Around the lake the local governor has posted guards and set up fires and warm baths to tempt them, but “an insurmountable barrier stands between them and the shore: the unseen Christ, whom they would have to deny to grasp the life that is leaving their bodies moment by moment” (Riciotti , 212). The soldiers pray that none of them will fail, that all 40 will gain the crown of martyrdom.

The bitter cold and the darkness of night take their toll. The faith of one falters, and he crawls for the bank, but when he is plunged in a bath the shock of the hot water takes his life. A pagan guard, inspired by the faith of the remaining 39, declares himself a Christian, strips off his clothes and runs onto the ice, restoring their number to 40. By morning they are all dead save the youngest, Meliton, who dies soon after in his mother’s arms.

The ordeal of the 40 Martyrs of Sebastia is the last snap of the dragon’s tail. Within three years Licinius will fall to Constantine’s armies. Eusebius casts the war between the two Augusti as a conflict in salvation history, with Constantine the champion of Christianity against Licinius, the last defender of the ancient pagan gods.

But there is more to the story. To be sure, it was Constantine who at last brought liberty to the early Church, but his edicts were not without precedent. It is a caricature to describe the first 300 years of the Church as an underground organization constantly persecuted by a hostile Roman state. While there were periods of terrible persecution, there were also lengthy periods of cooperation and convergence that culminated in Constantine’s Edict of Milan.

During the first decades of the Church, Christians in Palestine generally enjoyed the protection of Roman justice, which, as we know from the trial of our Lord, reserved to itself capital sentences and attempted not to interfere with the religions of the various peoples of the empire. The stoning of St. Stephen, for example, was one of the “occasional acts of brutal popular justice which were unauthorized but which the Roman authorities could not always prevent” (Marta Sordi, The Christians and the Roman Empire, 12).

Protected by TiberiusTertullian and Justin Martyr record that after the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ, Pontius Pilate reported to the emperor his frustration with the Sanhedrin because they reacted to the growth of Christianity with a series of illegal trials and executions.

Tertullian relates that Emperor Tiberius, after reading Pilate’s report, was so taken with the peaceful nature of the Christians that he proposed to the senate that Jesus Christ be added to the Roman pantheon. The Senate, perhaps because Tiberius was unpopular, rejected the proposal and declared Christianity a superstitio illicita, an illegal cult. Tiberius, hoping to free the Christians from the oppression of the Sanhedrin, undercut the law with a veto against any future accusations against Christians. The veracity of the story is debated by historians, but since it is the only written account of how Christianity came to be illegal, there is good reason to believe it.

Tiberius then sent an envoy to Judea to sack Caiaphus, the high priest of the Jews, probably for the crime of executing Stephen. The Acts of the Apostles reports that thereafter the “Church had peace throughout all Judea, Galilee, and Samaria” (Acts 9:31), the very three regions under Roman rule.

For the next three decades Christians enjoyed the protection of Tiberius’s veto, with two exceptions. First, from 41-44, the Romans surrendered rule of Judea to Herod Agrippa, during whose reign James the Greater became the first apostle to die for Christ. Herod Agrippa, seeing that his execution of James “pleased the Jews” (Acts 12:3), arrested and imprisoned Peter.

Second, during a subsequent absence of Roman rule in 62, James the Lesser, first Bishop of Jerusalem, was thrown from the roof of the temple, then stoned, then dealt the death blow to the head with a club. Jewish historian Flavius Josephus reports that the chief priest Ananius and the Sanhedrin were taking advantage of a temporary vacancy in the Roman governor’s seat.

Paul’s TreatmentIt is illustrative to look at the Romans’ treatment of Paul. He was brought before the Roman proconsul (Acts 18) and twice before the Roman procurator in Judea by the Jewish authorities (Acts 21, 23, 25). The Romans refused to intervene in a religious quarrel between Christians and Jews. It is in this atmosphere of something between tolerance and benevolence that Sergius Paulus, Roman proconsul of Cyprus, moved by the preaching of Paul and Barnabas, “learned to believe” (Acts 13:12). Sergius Paulus became a close friend of Paul, and his whole family converted.

Things do not turn dark for the Church until the reign of Nero, although not right away, for Paul is acquitted at his first trial, and continues to preach the gospel in the emperor’s household (Phil 1:13) and throughout the praetorium (Phil 4:22). His time there perhaps inspired the whole-armor-of-God imagery in Ephesians.

During the reign of Nero, a woman of the senatorial class, Poponia Graecina, a convert to Christianity, was declared innocent in a public trial. Pagan historian Tacitus reports that she continued her austere way of life and passed on her Christianity to her descendants. Other prominent families of the aristocratic classes were Christian: The Pudens family housed and fed Peter, and their home on the Esquiline hill is the site of Santa Pudenziana today.

Nero FiddlesWhen rumors that Nero started the great fire of 64 would not go away, he chose an easy scapegoat: the Christian community in Rome. Christians were not universally liked. Their strict moral code may explain why they were accused of, as Tacitus puts it, “hatred of the human race.” Peter describes pagans slandering Christians for their unwillingness to participate in “lawless disorders” (1 Pt 4:4). Pagan and Jewish enemies spread wild stories of criminal activities. “They will speak ill of you as workers of evil deeds,” writes Peter (1 Pt 2:12). We know from contemporary sources what these evil deeds were: human sacrifice and cannibalism (deliberate misrepresentations of the Eucharist) and incest (a deliberate twisting of the Christian practice of calling one another brother and sister).

The Roman historian Lactantius blames Nero’s persecutions on the growing number of Romans who were abandoning the worship of idols for the new religion. The fire may have accelerated persecutions that were already gaining steam. Paul seems to have been martyred before the fire and Peter after.

When the storm broke, the first persecution was brutal. Tacitus, no friend of the Christians, reports:

" ... Yet no human effort, no princely largess nor offerings to the gods could make that infamous rumor disappear that Nero had somehow ordered the fire. Therefore, in order to abolish that rumor, Nero falsely accused and executed with the most exquisite punishments those people called Christians . . . And perishing, they were additionally made into sports: They were killed by dogs by having the hides of beasts attached to them, or they were nailed to crosses or set aflame, and, when the daylight passed away, they were used as nighttime lamps. . . . [P]eople began to pity these sufferers, because they were consumed not for the public good but on account of the fierceness of one man. (Annals, 44.2-44.5) ... "

Nero, by allowing Christians to be accused of superstitio illicita, created a legal precedent that until then had only existed on the books. The first two rulers of the Flavian dynasty, Vespasian and his son Titus, however, rejected emperor-worship and tolerated the growing number of Christians, even in their own households. Vespasian’s brother, Flavius Sabinus, was one. Vespasian had come to know Christianity during his time in Palestine, where he concluded that Christians were not a political threat to the empire.

When Vespasian’s second son Domitian (81-96) revived the idea of the emperor as a god, he reignited the persecution of Christians, killing his own cousin, Flavius Clemens, a consul. Domitian’s persecutions coincide with the writing of Revelation, thus: the woman “drunk with the blood of the martyrs of Jesus” (Rv 17:6). Domitian’s successors, from Nerva to Marcus Aurelius (96-161), maintained laws against Christianity, but did not undertake any general campaign of persecution.

Pliny’s PlightWe get a glimpse into relations between the Church and the empire during the reign of Trajan (98-117). Trajan was a great soldier and hardworking administrator. When troubles broke out in the province of Bithynia, he sent Pliny the Younger to troubleshoot. Their correspondence resulted in the famous document all good Latin students know as Trajan’s Rescript.

Pliny explains that Christianity is quite popular among people of all classes and ages, urban and rural, and because so many have converted, the temple-sacrifice business is down. Christians had made enemies of not only pagan priests but also livestock dealers. Because he has “never participated in trials of Christians,” Pliny does not know what “offenses it is the practice to punish or investigate.” Is age a factor? Should pardon be granted for repentance? He asks, “whether the name itself, even without offenses, or only the offenses associated with the name are to be punished.”

He outlines the procedure he has been following when accusations are brought before him. He interrogates the accused, and if he or she confesses, he repeats the questioning several times in hopes of gaining repentance. The stubborn were executed, though Roman citizens were transferred to Rome, as Paul had been. Pliny is disdainful of anonymous accusations, and he finds no evidence of actual wrongdoing in Christian ceremonies:

" ... They were accustomed to meet on a fixed day before dawn and sing together a hymn to Christ as to a god, and to bind themselves by oath, not to some crime, but not to commit fraud, theft, or adultery, not falsify their trust, nor to refuse to return a trust when called upon to do so. When this was over, it was their custom to depart and to assemble again to partake of food—but ordinary and innocent food. (Letters 10) ... "

Trajan responds:

" ... You observed proper procedure, my dear Pliny, in sifting the cases of those who had been denounced to you as Christians. For it is not possible to lay down any general rule to serve as a kind of fixed standard. They are not to be sought out (Conquirendi non sunt); if they are denounced and proved guilty, they are to be punished, with this reservation, that whoever denies that he is a Christian and really proves it—that is, by worshiping our gods—even though he was under suspicion in the past, shall obtain pardon through repentance. But anonymously posted accusations ought to have no place in any prosecution. For this is both a dangerous kind of precedent and out of keeping with the spirit of our age. ..."

So, from the Roman perspective, the practice of Christianity carried the death penalty, but Trajan does not seek reasons to execute people. No effort was to be made to seek them out and no anonymous accusations could lead to an arrest. This is Roman bureaucracy at its best and at its worst. Trajan and Pliny are dedicated public servants laboring under legal precedents that could lead to the killing of innocent men. Trajan cannot repudiate a law from the reign of Tiberius, but he devises a lenient interpretation for Pliny to follow.

During this era a Christian could be ratted out, but informers were thought ill of in Roman society, and they ran the risk of bringing down the full weight of Roman justice on themselves should their accusations go unproved. Thus, persecutions varied by region. In an area with a large Christian population like Bithynia, only a fool would openly denounce a neighbor, so Christians who followed Paul’s injunction not deliberately to seek martyrdom enjoyed relative security.

Immigrants Fare WorseIn Lyons, however, matters were far worse. There is a correspondence between Emperor Marcus Aurelius and the Roman officials in Lyons similar to Trajan’s rescript, but in this region where the Christian population comprised immigrants from Asia Minor, they were despised by the local Gallic population.

The account of the Lyons Martyrs, a contemporary letter copied by Eusebius, describes the horrifying ordeals of the leaders of this Christian community (most famous is Bl. Blandina) including:

" ... confinement in the darkest and most foul-smelling cells of the prison . . . in which a great many suffocated . . . the stretching of the feet on the stocks . . . the fixing of red-hot plates of brass to the most delicate parts of the body . . . exposure to wild beasts and roasting over a fire in an iron chair. (Church History V) ... "

The next emperor, Commodus, was the depraved adopted son of Marcus Aurelius. But even at his court there were Christians. His concubine, Marcia, who later conspired in his murder, was sympathetic to Christianity. By her intervention, Christian slaves were set free from the mines of Sardinia.

Trajan’s rescript remained the law during the reign of Septimius Severus (193-211) who sought to check the growth of Christianity by making conversion a crime. The famous convert martyrs of this period, mentioned in the Canon of the Mass, are Sts. Perpetua and Felicitas of Carthage.

Beginning with the reign of Caracalla (211-217), Christians enjoyed peace. There was even a Christian emperor during this period. Philip the Arab has been regarded as one of the empire’s worst emperors, but the opinion may be more the result of subsequent anti-Christian propaganda than an honest account of his administration, which lasted five years, unusually long for this period of unrest. He was murdered by Decius (249-251) who probably killed his reputation as well.

Plagued by barbarian invasions, Decius believed that the growth of the Christian sect was bringing down disfavor from the gods, so he issued an edict requiring all Christians to offer sacrifice to the pagan deities. Valerian (253-260) opened an empire-wide series of persecutions, and it is during this age that the patron of altar boys, Tarcisius, gave his life (see “Tarcisius,” page 11).

Two decades later, Emperor Aurelian (who built much of the wall surrounding Rome today) tolerated Christianity and even intervened in a dispute over ownership of a Church building in Antioch, ruling in favor of those Christians who were in union with the Bishop of Rome! Though the worst was yet to come under Diocletian, the way was already being cleared for peaceful coexistence.

At First, PeaceThe bloodiest, and best documented, of the great persecutions came under Diocletian (284-305), though this emperor for whom the persecution is remembered was not, at first, its instigator. For most of Diocletian’s reign, Christians enjoyed peace and prosperity.

Diocletian was a courageous general. His political innovation, the tetrarchy, which divided rule of the massive Roman Empire between two augusti, one in the east and one in the west, and their caesars, or executive officers, restored order to an empire that had for five decades suffered chaos, rebellious legionaries, praetorians in revolt, and civil war. Of the 28 emperors who had preceded Diocletian, 22 had been murdered.

He moved the imperial capital from Rome to Nicomedia, near the Bosporus, on the grounds that the emperor was most needed on the frontier. Under Diocletian, building and public works began again in earnest throughout the empire, including the extraordinary baths named for him in Rome. He brought inflation under control. He even issued an edict promoting the institution of marriage, holding that chastity would draw down the favor of the gods on the empire. At the end of his reign, the old emperor abdicated and went off to his farm to grow cabbages.

There were Christians in Diocletian’s household. His wife, Prisca, and his daughter, Valeria, were catechumens. Officers of his court, including two chamberlains appointed by Diocletian himself, Gorgonius and Peter, were openly Christian. What is more, Diocletian had appointed Christians as governors of various provinces.

Diocletian’s caesar Galerius, however, was a lesser soldier and a man of lesser character altogether, though a skilled self-promoter. A violent and very large man, he rose from illiterate shepherd to caesar, and eventually to Augustus in the east, following Diocletian’s abdication. Diocleatian gave him his daughter, Valeria, in marriage.

It was not Valeria, however, but Galerius’ mother, a Corybantic priestess, who had influence on Galerius. She and other diviners, oracles, and soothsayers had seen—as in Trajan’s day—their businesses suffer as Christianity spread throughout the empire. Galerius also took to heart the work of pagan pamphleteers who argued that Christianity’s explicit rejection of the traditional Roman deities threatened the empire. Galerius viewed Christians serving in the army as a threat to unit cohesion and discipline, though there is no evidence that this was anything more than prejudice. (Many soldiers lost their lives during these persecutions, including St. Sebastian and St. George.)

The Worst BeginsAt first Diocletian was reluctant to open a new round of persecutions. By this stage, Christians were well integrated into all levels of Roman society, and he saw persecution as politically unwise. When at last Galerius prevailed on the old emperor, the result was a series of four edicts beginning in 302, each more severe than the one before.

Eusebius reports that this first edict ordered the destruction of churches and the burning of Sacred Scripture. It also required the degrading of men of station who were Christian. The subsequent three edicts ordered the imprisonment of bishops and clergy, then the torture of imprisoned bishops and clergy, and finally the torture and imprisonment of the laity.

This persecution was fierce and empire-wide. Martyrs in Egypt, for example, had their legs tied to two young trees bent toward each other and then allowed to snap back, tearing the victim in half. The persecution continued in the east throughout Galerius’ reign and through that of Licinius, under whom the 40 Martyrs of Sebastia were frozen to death.

TriumphThe triumph of Constantine brought the persecutions to a close with the exception of a brief period half a century later under Julian the Apostate.

As we have seen, the common conception that Christians for the first 300 years were outlaws perpetually hounded by a hostile state is not accurate. There were periods of brutal persecution and also periods of peace. Most persecutions were local. Only two were empire-wide, those of Valerian and Diocletian. In the case of Diocletian’s persecutions, Constantius, father of Constantine, did not participate, leaving Britain, Gaul, and much of Spain at peace. With the exception of the persecutions under Nero, the systematic and horrible persecutions took place in the provinces, not in Rome.

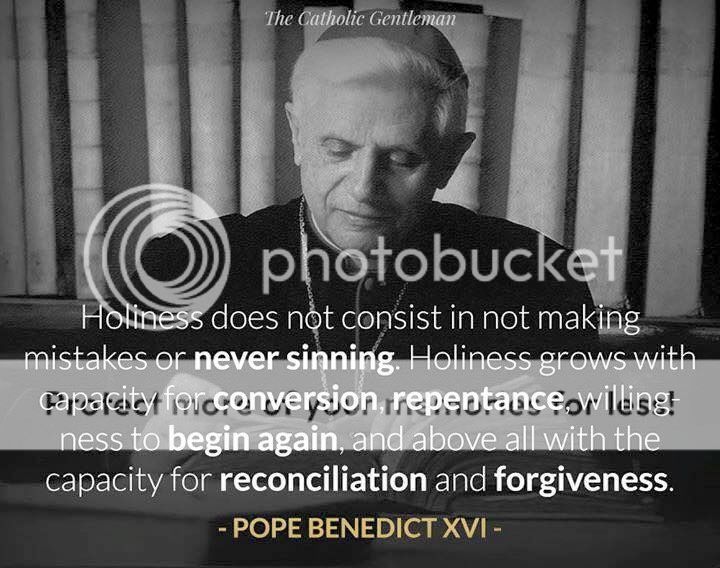

These facts in no way detract from the heroism of the martyrs whose privations and tortures are good to recall when the inconveniences of daily life move us to self-pity. The charity of the martyrs for their torturers bears reflection when we encounter the periodic jerk. Pope John Paul II puts it more eloquently in Veritatis Splendor:

" ... Although martyrdom represents the high point of the witness to moral truth, and one to which relatively few people are called, there is nonetheless a consistent witness which all Christians must daily be ready to make, even at the cost of suffering and grave sacrifice. Indeed, faced with the many difficulties which fidelity to the moral order can demand, even in the most ordinary circumstances, the Christian is called, with the grace of God invoked in prayer, to a sometimes heroic commitment. (93) ... "

John Paul emphasizes that martyrs are a witness to moral clarity:

" ... By witnessing fully to the good, they are a living reproof to those who transgress the law (cf. Wis 2:12), and they make the words of the prophet echo ever afresh: “Woe to those who call evil good and good evil, who put darkness for light and light for darkness, who put bitter for sweet and sweet for bitter!” (Is 5:20) (VS 93) ... "

In this age when tolerance is touted as the highest good, it is well to remember that the early martyrs were not martyrs to the cause of religious tolerance. They were martyrs for the First Commandment. Roman rule was so successful partly because of its ability to reconcile so many beliefs and so many gods—to the satisfaction of most of its citizens. That entrenched syncretism reacted with everything from ridicule to rage to a Christianity that insisted on One God in Three Persons before whom there were no others. No early Christian said to his pagan friend, “You call him Sol Invictus and I call him Jesus Christ, but we basically worship the same God.”

Religious tolerance of a practical sort has political value, as more than one Roman official learned, but dogmatic tolerance is a sin against truth, and those who cannot see this distinction cannot defend their faith. A time may be fast approaching, however, when they will be called into circuses the horror of which will rival Nero’s. The difference will be no periods of relief from the order of Roman law.

SIDEBARSTarcisiusWhen the emperor Valerian ordered the execution of bishops, priests, and deacons, Christians attended Mass in basements and in the catacombs outside the city walls. Deacons would take Communion to Christians for whom getting to Mass was too dangerous.

On one such occasion, no deacon was available. The priest did not know what he would do until his altar boy, a young Roman boy of 11 named Tarcisius, stepped forward after Mass and said that he would carry Communion to some Christians waiting inside the city walls. The priest admired Tarcisius for his grit, gave him the Sacred Hosts wrapped in silk along with a quick blessing, and sent him toward the city.

All was going well until Tarcisius ran into some pagan boys his own age who asked him to come and join their game. Tarcisius thanked them, explained he had an errand to run, but said he would join them later.

“Oh! Christian boy!” One of the pagan boys sneered. “Is it that you think you are too good to play with us?” And they circled around Tarcisius.

“Not at all,” said Tarcisius. “I have something to deliver and must be on my way.”

“Well—show us what it is! What is the big secret, Christian boy?”

“It is no business of yours,” said Tarcisius, looking each of the boys squarely in the eye. “Now step aside and make way.”

Rather than step aside, the pagan boys closed their circle around Tarcisius, and as they did they picked up heavy sticks and rocks from the ground. One of them shouted, “I bet he's carrying the Christian Mysteries!”

“Are you, Christian boy?” demanded another. “Show us!”

Tarcisius, clutching his precious cargo to his chest made a dash for what looked like an opening in the circle, but he was not quick enough. The mob of boys closed around him and they began to club him with the stones and heavy sticks. Tarcisius did not cry out, but quietly prayed, ever clutching the Blessed Sacrament to his chest.

The pagan boys beat him to death.

With bloodied hands, they seized the bruised and broken body of Tarcisius and tried to twist the silk cloth carrying the Eucharist out of his dead arms. Although he had no life left in him, Tarcisius would not let go of our Lord. The boys tried for hours to pry his arms open but they failed and failed again. They left Tarcisius’s body by the side of the road for the vultures to eat.

After a time, some Christians went looking for Tarcisius, and when they found his broken and bloody corpse still clinging to the Blessed Sacrament, they guessed what had happened. Carefully lifting the small boy’s body, they gently bore it back to the priest, who by now had grown deeply concerned about his young altar boy. The Christians set the boy’s body at the foot of the priest, who knelt down and quietly brushed Tarcisius’s hair, matted with blood, away from his face and with his thumb made the Sign of the Cross on his forehead. At that moment, Tarcisius’s body unfolded its arms and released the Blessed Sacrament to the priest, and all who witnessed this knew that here was a holy Christian boy who had held Jesus in his arms and who now was being held forever in the arms of Jesus.

Reigns of Relevant Roman EmperorsTiberius 14-37

Nero 54-68

Vespasian 69-79

Titus 79-81

Domitian 81-96

Trajan 98-117

Marcus Aurelius 161-180

Commodus 180-192

Septimius Severus 193-211

Caracalla 211-217

Phillip the Arab 244-249

Decius 249-251

Valerian 253-260

Aurelian 270-275

Diocletian 284-305

Licinius 308-324

Constantine 306-337

Julian the Apostate 355-363

Source:

http://www.catholic.com/magazine/articles/...he-early-churchThis post has been edited by khool: Jul 21 2015, 02:13 PM

Jul 20 2015, 11:26 AM

Jul 20 2015, 11:26 AM

Quote

Quote

0.1344sec

0.1344sec

0.60

0.60

7 queries

7 queries

GZIP Disabled

GZIP Disabled