QUOTE

On a cool Sunday evening in March, a geochemist named Sun Weidong gave a public lecture to an audience of laymen, students, and professors at the University of Science and Technology in Hefei, the capital city of the landlocked province of Anhui in eastern China. But the professor didn’t just talk about geochemistry. He also cited several ancient Chinese classics, at one point quoting historian Sima Qian’s description of the topography of the Xia empire — traditionally regarded as China’s founding dynasty, dating from 2070 to 1600 B.C. “Northwards the stream is divided and becomes the nine rivers,” wrote Sima Qian in his first century historiography, the Records of the Grand Historian. “Reunited, it forms the opposing river and flows into the sea.”

In other words, “the stream” in question wasn’t China’s famed Yellow River, which flows from west to east. “There is only one major river in the world which flows northwards. Which one is it?” the professor asked. “The Nile,” someone replied. Sun then showed a map of the famed Egyptian river and its delta — with nine of its distributaries flowing into the Mediterranean. This author, a researcher at the same institute, watched as audience members broke into smiles and murmurs, intrigued that these ancient Chinese texts seemed to better agree with the geography of Egypt than that of China.

In the past year, Sun, a highly decorated scientist, has ignited a passionate online debate with claims that the founders of Chinese civilization were not in any sense Chinese but actually migrants from Egypt. He conceived of this connection in the 1990s while performing radiometric dating of ancient Chinese bronzes; to his surprise, their chemical composition more closely resembled those of ancient Egyptian bronzes than native Chinese ores. Both Sun’s ideas and the controversy surrounding them flow out of a much older tradition of nationalist archaeology in China, which for more than a century has sought to answer a basic scientific question that has always been heavily politicized: Where do the Chinese people come from?

Sun argues that China’s Bronze Age technology, widely thought by scholars to have first entered the northwest of the country through the prehistoric Silk Road, actually came by sea. According to him, its bearers were the Hyksos, the Western Asian people who ruled parts of northern Egypt as foreigners between the 17th and 16th centuries B.C., until their eventual expulsion. He notes that the Hyksos possessed at an earlier date almost all the same remarkable technology — bronze metallurgy, chariots, literacy, domesticated plants and animals — that archaeologists discovered at the ancient city of Yin, the capital of China’s second dynasty, the Shang, between 1300 and 1046 B.C. Since the Hyksos are known to have developed ships for war and trade that enabled them to sail the Red and Mediterranean seas, Sun speculates that a small population escaped their collapsing dynasty using seafaring technology that eventually brought them and their Bronze Age culture to the coast of China.

In other words, “the stream” in question wasn’t China’s famed Yellow River, which flows from west to east. “There is only one major river in the world which flows northwards. Which one is it?” the professor asked. “The Nile,” someone replied. Sun then showed a map of the famed Egyptian river and its delta — with nine of its distributaries flowing into the Mediterranean. This author, a researcher at the same institute, watched as audience members broke into smiles and murmurs, intrigued that these ancient Chinese texts seemed to better agree with the geography of Egypt than that of China.

In the past year, Sun, a highly decorated scientist, has ignited a passionate online debate with claims that the founders of Chinese civilization were not in any sense Chinese but actually migrants from Egypt. He conceived of this connection in the 1990s while performing radiometric dating of ancient Chinese bronzes; to his surprise, their chemical composition more closely resembled those of ancient Egyptian bronzes than native Chinese ores. Both Sun’s ideas and the controversy surrounding them flow out of a much older tradition of nationalist archaeology in China, which for more than a century has sought to answer a basic scientific question that has always been heavily politicized: Where do the Chinese people come from?

Sun argues that China’s Bronze Age technology, widely thought by scholars to have first entered the northwest of the country through the prehistoric Silk Road, actually came by sea. According to him, its bearers were the Hyksos, the Western Asian people who ruled parts of northern Egypt as foreigners between the 17th and 16th centuries B.C., until their eventual expulsion. He notes that the Hyksos possessed at an earlier date almost all the same remarkable technology — bronze metallurgy, chariots, literacy, domesticated plants and animals — that archaeologists discovered at the ancient city of Yin, the capital of China’s second dynasty, the Shang, between 1300 and 1046 B.C. Since the Hyksos are known to have developed ships for war and trade that enabled them to sail the Red and Mediterranean seas, Sun speculates that a small population escaped their collapsing dynasty using seafaring technology that eventually brought them and their Bronze Age culture to the coast of China.

QUOTE

China's historical records are very long. 100 years ago, the Chinese people knew more about Chinese ancestors coming from the West, but the Qing government stopped research on this issue. Over the past decade, this issue has been rediscussed in China. Su San and Liu Guangbao both wrote books to demonstrate that ancient Egypt are the Chinese Xia Dynasty.

Egyptian ‹mỉw› ‘cat’ — Mandarin 貓 (māo) ‘cat’

Sahidic Coptic ⲧⲱⲃⲉ /tōbe/ ‘brick’ — Mandarin 土坯 (tǔpī) ‘mud brick, adobe’

Egyptian ‹rꜥ› ‘sun, Ra’ — Mandarin 日 (rì) ‘sun, day’

Egyptian ‹mw.t› ‘mother’ — Mandarin 母 (mǔ) ‘mother’

Egyptian ‹tꜣ› ‘land, realm’ — Old Chinese 土 *t�ˤa� ‘earth’

Egyptian ‹ꜣpd› ‘birds, water fowl’ — Cantonese 鴨 (aap) ‘duck’

Coptic ϩⲟ /ho/ ‘face’ — Haikou Minnan 头 /hau̯˧˩/ ‘head’

Egyptian ‹bỉt› ‘honey’ — Hokkien 蜜 (bi̍t) ‘honey’

Egyptian ‹hꜣỉ› ‘to fall’ — Shantou Minnan 下 /hi̯a˧˥/ ‘to fall’

Egyptian ‹ḫꜥỉ› ‘to shine’ — Mandarin 輝 (huī) ‘brightness; to shine upon’

Egyptian ‹sꜣ› ‘son’ — Old Chinese 子 *tsə� ‘child, son’

Egyptian ‹ṯs› ‘sentence’ — Mandarin 句子 (jùzi) ‘sentence’

Egyptian ‹ḏw› ‘to be bad’ — Mandarin 臭 (chòu) ‘bad smell; to be bad’

Late Egyptian ‹pr ꜥꜣ› ‘pharaoh’ (lit. ‘big house’) — Mandarin 法老 (fǎlǎo) ‘pharaoh’

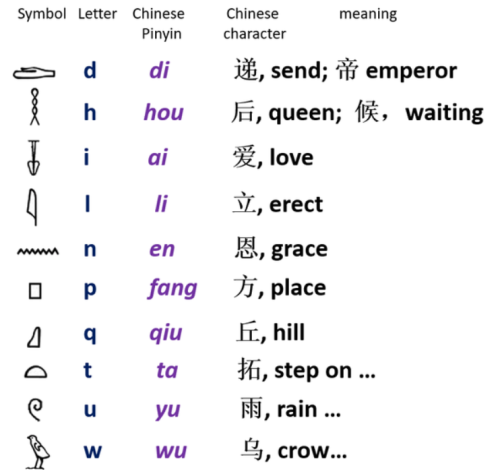

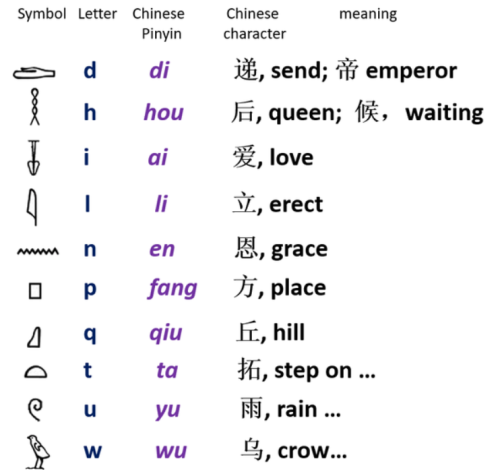

The best way to prove this idea is to decipher ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs using Chinese as the key. Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs are Chinese v1.0. Using Chinese pronunciations and historical materials to investigate ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, the early history of mankind, and the Xia Dynasty in China appear.

Egyptian ‹mỉw› ‘cat’ — Mandarin 貓 (māo) ‘cat’

Sahidic Coptic ⲧⲱⲃⲉ /tōbe/ ‘brick’ — Mandarin 土坯 (tǔpī) ‘mud brick, adobe’

Egyptian ‹rꜥ› ‘sun, Ra’ — Mandarin 日 (rì) ‘sun, day’

Egyptian ‹mw.t› ‘mother’ — Mandarin 母 (mǔ) ‘mother’

Egyptian ‹tꜣ› ‘land, realm’ — Old Chinese 土 *t�ˤa� ‘earth’

Egyptian ‹ꜣpd› ‘birds, water fowl’ — Cantonese 鴨 (aap) ‘duck’

Coptic ϩⲟ /ho/ ‘face’ — Haikou Minnan 头 /hau̯˧˩/ ‘head’

Egyptian ‹bỉt› ‘honey’ — Hokkien 蜜 (bi̍t) ‘honey’

Egyptian ‹hꜣỉ› ‘to fall’ — Shantou Minnan 下 /hi̯a˧˥/ ‘to fall’

Egyptian ‹ḫꜥỉ› ‘to shine’ — Mandarin 輝 (huī) ‘brightness; to shine upon’

Egyptian ‹sꜣ› ‘son’ — Old Chinese 子 *tsə� ‘child, son’

Egyptian ‹ṯs› ‘sentence’ — Mandarin 句子 (jùzi) ‘sentence’

Egyptian ‹ḏw› ‘to be bad’ — Mandarin 臭 (chòu) ‘bad smell; to be bad’

Late Egyptian ‹pr ꜥꜣ› ‘pharaoh’ (lit. ‘big house’) — Mandarin 法老 (fǎlǎo) ‘pharaoh’

The best way to prove this idea is to decipher ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs using Chinese as the key. Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs are Chinese v1.0. Using Chinese pronunciations and historical materials to investigate ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, the early history of mankind, and the Xia Dynasty in China appear.

chinese pyramids

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_pyramids

https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1007903

QUOTE

The sketchy historical record has left room for more esoteric theories about Sanxingdui to flourish. For years, a conspiracy theory claiming the site is the remains of an alien civilization has been circulating in China.

According to this theory, extra-terrestrials came to Earth over 5,000 years ago and built a string of settlements along the 30th parallel north. This led to the creation of the Egyptian pyramids, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Mayan civilization, as well as the lost city in Sichuan province. The aliens then exited the planet through a wormhole in Bermuda, the story goes.

Despite carbon dating showing the sacrificial pits were made 2,000 years after the aliens’ supposed stay on Earth, the alien hypothesis has gained significant traction on the Chinese internet.

A more reasonable theory posits that Sanxingdui was founded by foreign settlers. Zhu Dake, a renowned cultural scholar affiliated with Shanghai’s Tongji University, has suggested the city was built by travelers from the Middle East or ancient Egypt.

According to this theory, extra-terrestrials came to Earth over 5,000 years ago and built a string of settlements along the 30th parallel north. This led to the creation of the Egyptian pyramids, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Mayan civilization, as well as the lost city in Sichuan province. The aliens then exited the planet through a wormhole in Bermuda, the story goes.

Despite carbon dating showing the sacrificial pits were made 2,000 years after the aliens’ supposed stay on Earth, the alien hypothesis has gained significant traction on the Chinese internet.

A more reasonable theory posits that Sanxingdui was founded by foreign settlers. Zhu Dake, a renowned cultural scholar affiliated with Shanghai’s Tongji University, has suggested the city was built by travelers from the Middle East or ancient Egypt.

This post has been edited by likefunyouare: Jul 6 2023, 03:12 AM

Jul 6 2023, 03:12 AM, updated 3y ago

Jul 6 2023, 03:12 AM, updated 3y ago

Quote

Quote

0.0391sec

0.0391sec

0.44

0.44

5 queries

5 queries

GZIP Disabled

GZIP Disabled