侠骨柔情留天地 , 剑胆琴心付云霄

永远的武林盟主

金庸(1924-2018)

2018年的10月30日,94岁的金庸仙逝,随手带走了一个属于武侠、属于过往,也属于青春的时代。

《射雕》有五绝:

“东邪”黄药师、

“西毒”欧阳锋、

“南帝”一灯、

“北丐”洪七公、

“中神通”王重阳。

15部小说的书名大致分为4类:

刀剑系列:

《碧血剑》、《鸳鸯刀》、《越女剑》;

诀谱诗系列:

《笑傲江湖》、《侠客行》;《连城诀》、

传记录系列:

《射雕英雄传》、《神雕侠侣》、《倚天屠龙记》、

《鹿鼎记》、《书剑恩仇录》;《飞狐外传》、

人或动物名称系列:

《天龙八部》、《雪山飞狐》、《白马啸西风》

/---------/---------------/------/---------/

| 序号 | 分类 | 作品 | 帮派 | 人物 | 武功 | 地点 |

| 1 | **刀剑系列** | **碧血剑** | 何铁手:五毒教教主,后拜袁承志为师,改名何惕守,武功略逊于木桑,玉真子,穆人清以及他三大弟子,亦在《鹿鼎记》中出现。为《鹿鼎记》中双儿的师父。夏青青:小说女主角。为夏雪宜和温仪的女儿,个性较为任性,是个醋坛子。与袁承志结成连理。袁承志之妻。阿九:长平公主,崇祯皇帝的女儿,出家后为独臂神尼九难师太,后在《鹿鼎记》中出现。为《鹿鼎记》中阿珂的师父。 | 袁承志、岳灵珊 | 金蛇剑法及金蛇锥 | 江湖 |

| 2 | **刀剑系列** | **鸳鸯刀** | 江湖群雄 | 萧中慧、袁冠南、林玉龙、任飞燕 | 震天三十掌,呼延十八鞭 | 最终揭露“鸳鸯刀”的秘密原来是“仁者无敌”。 |

| 3 | **刀剑系列** | **越女剑** | 东海海盗、百花谷 | 范蠡、越王勾践、王异 | 越女剑法、剑气 | 越国、吴国、江南 |

| 4 | **诀谱诗系列** | **笑傲江湖** | 华山派、日月神教、嵩山派、少林派 | 令狐冲、任盈盈、岳灵珊、林平之、左冷禅 | 独孤九剑、辟邪剑法、九阳神功 | 华山、少林寺、衡山、无量山 |

| 5 | **诀谱诗系列** | **侠客行** | 天山派、百花谷、江湖群雄 | 石破天、裘千仞 | 无影剑法、石破天拳、天山六阳掌 | 大理、天山、江湖 |

| 6 | **诀谱诗系列** | **连城诀** | 暗影门、少林派 | 狄云、林振荣、王佳芝 | 连城剑法、九阳神功、飞影术 | 江南、华山、少林 |

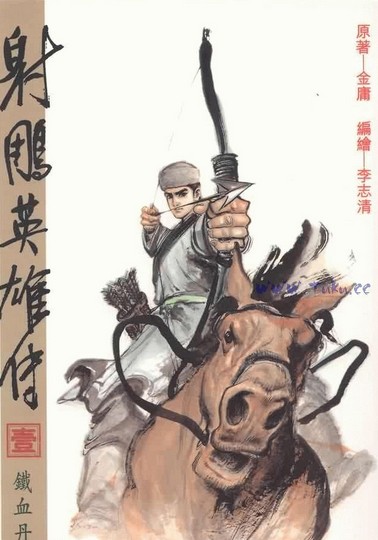

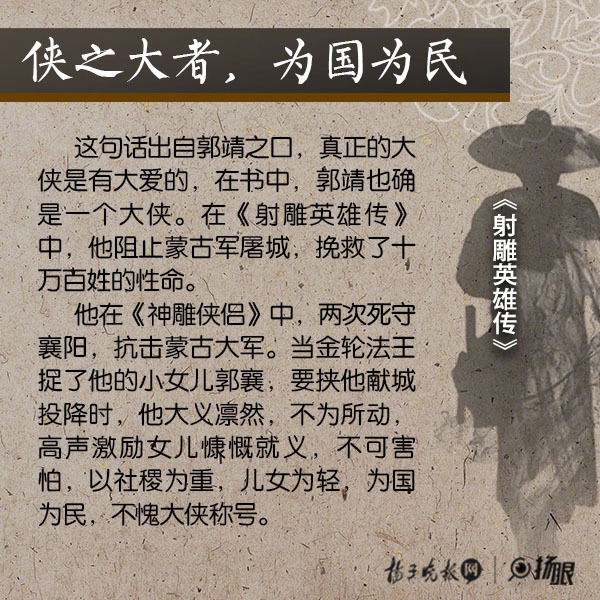

| 7 | **传记录系列** | **射雕英雄传** | 丐帮、桃花岛、天龙门、少林派 | 郭靖、黄蓉、杨康、欧阳锋、洪七公 | 降龙十八掌、九阳神功、九阴真经、飞狐三式 | 桃花岛、光明顶、岳阳楼、乔家大院、少林寺 |

| 8 | **传记录系列** | **神雕侠侣** | 丐帮、全真教、古墓派 | 杨过、小龙女、郭靖、黄蓉、金轮寺大法师 | 神雕拳、九阳神功、黯然销魂掌 | 绝情谷、桃花岛、神雕山、古墓、重阳宫 |

| 9 | **传记录系列** | **倚天屠龙记** | 明教、波斯总教,武当派、峨眉派、少林派 | 张无忌、赵敏【“汝阳王”察罕特穆尔之女】、范遥(苦头陀), 张三丰,杨逍、殷天正, 周芷若、谢逊,成昆,宋青书 | 周芷若凭借速成版九阴白骨爪、九阳神功,武当绵掌,玄冥神掌,金刚般若掌 ,七伤拳,达摩剑法,大力金刚指,少林七十二绝技之一,*****渡劫、渡难、渡厄****三僧共坐枯禅练成的鞭法阵式,以“金刚经”为最高旨义,最后要达“无我相,无人相,无众生相,无寿者相”,于人我之分,生死之别,尽皆视作空幻。三位少林高僧枯禅数十年坐将下来,寒冰绵掌,狮子吼,心意相通,一僧招数中露出破绽空隙,其余二僧立即予以补足,飘雪穿云掌,(佛光普照,峨嵋派掌法)乾坤大挪移、六脉神剑、武当剑法,九阴真经 | 光明顶、武当山、峨眉山、大理、少林寺 |

| 10 | **传记录系列** | **鹿鼎记** | 天地会、天地会青木堂,东厂、神龙教 | 韦小宝、皇帝、(七名夫人:建宁公主,沐剑屏,方怡,双儿,苏荃,曾柔,阿珂、)吳三桂,宫中:海大富,多隆,张康年,李自成 (神龙教:教主洪安通,假皇太后毛东珠,瘦头陀,胖头陀,陆高轩) | 打狗棒法、九阳真经、葵花宝典 ,《四十二章经》 | 北京、扬州、杭州、江南 |

| 11 | **传记录系列** | **书剑恩仇录** | 红花会、东厂、山西帮 | 陈家洛 ( 男 ) —— 男主角,汉人官员陈世倌第三子,红花会总舵主于万亭之义子。师从天池怪侠袁士霄,武器为九条珠索(打穴)和剑盾,后继任于万亭为总舵主,「黑無常」常赫志、「白無常」常伯志,二人為孿生兄弟,合稱「西川雙俠」,外貌幾乎一模一樣,唯一人面有黑痣而另一人無。二人師承四川青城派掌門慧侶道人,武功高強,擅使黑沙掌,輕功超卓,兵刃為一對飛抓,卓文君、胡斐、何铁手、李沅芷 | 九阴真经、降龙十八掌、无影脚 | 江南、山西、北京 |

| 12 | **传记录系列** | **飞狐外传** | 武林各派、雪山派、江湖群雄 | 胡斐、苗若兰、程灵素、白云飞 | 飞狐三式、独孤九剑 | 山西、江南、雪山 |

| 13 | **人或动物名称系列** | **天龙八部** | 丐帮、段氏王朝、少林派、天山派 | 乔峰(萧峰)、段誉、虚竹、王语嫣、阿紫 | 降龙二十八掌、天山六阳掌、北冥神功,六脉神剑,凌波微步 , 八荒六合唯我独尊功 | 大理、少林寺、天山、光明顶、江南 |

| 14 | **人或动物名称系列** | **雪山飞狐** | 藏族、苗疆派 | 胡斐—— 本作品第二男主角,「遼東大俠」胡一刀之子,江湖人稱「雪山飛狐」。喜歡苗若蘭,苗人鳳、主角胡斐之父胡一刀,外号“打遍天下无敌手”,人称“金面佛”,闯王四大护卫苗姓护卫后裔,田歸農,后来苗人凤被官府通缉,与家人一直过着漂泊不定的生活。,闖王李自成 | 飞狐三式、九阳神功、天山六阳掌 | 雪山、苗疆、江南 |

| 15 | **人或动物名称系列** | **白马啸西风** | 中原各派 | 李文秀——小说主角之一,長居新疆大漠,跟蘇普有青梅竹馬之情誼,但後不忍蘇普被他父親虐打,所以用計令蘇普對自己死心。後成華輝的徒弟,華輝——『一指震江南』;李文秀、馬家駿 (計老人) 的師父,原本是哈薩克族人瓦耳拉齊。最終與馬家駿在高昌迷宮內同歸於盡,白馬李三——李文秀父親,小说剛开头时即喪命,上官虹『金銀小劍三娘子』——李文秀母親,小說剛開頭時即喪命。 | 剑法、柔功、空明拳 | 西北边疆、江湖 |

1966年,极左风潮蔓延至香港,左派宣称金庸是“豺狼镛”,并扬言:

“要消灭五个香港人,排名第二的就是金庸。”

此后,左派甚至自制炸弹放在明报报社,并煽动《明报》内部员工“起义”袭击报社。但尽管饱受冲击,《明报》的发行量不减反增,从日发行5万份飙涨至8万份。

面对左派的刺杀威胁,金庸后来回忆说:

“我虽然成为暗杀目标,生命受到威胁,内心不免害怕,但我决不屈服于无理的压力之下,以至被我书中的英雄瞧不起。”

各方压力下,1972年,正值写作壮年的48岁金庸,在写完武侠寓言《鹿鼎记》后宣布封笔。

提拔施琅

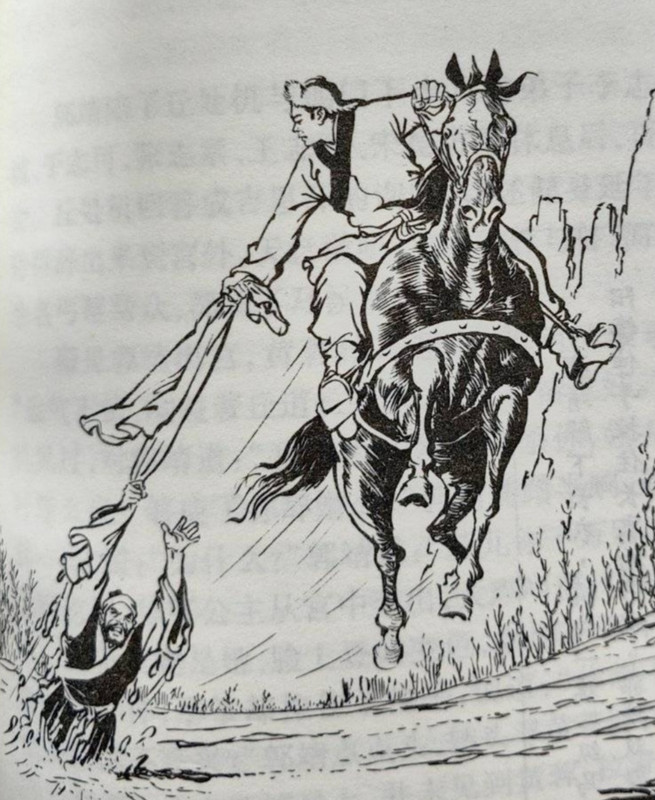

施琅在京遭到投闲,得韦小宝提拔,方为康熙起用,后来才能担任征台司令,消灭南明(明郑)。

韦小宝后来以危言威胁施琅带他到台湾,又指点施琅如何阻止朝廷弃守台湾。

《射雕三部曲》是当代著名作家金庸著作分为

《射雕英雄传》《神雕侠侣》《倚天屠龙记》三部武侠小说的合称。

新修版《天龙八部》再次呼应这一改写,在第三十三回增加了以下描写——

“丐帮神功降龙十八掌,在北宋年间本为二十八掌,

当时帮主萧峰武功盖世,却因契丹人身份遭驱除出帮,

他去繁就简,将二十八掌减了十掌,成为降龙十八掌,

由义弟灵鹫宫虚竹子代传,由此世代传承。

到南宋末年,虽继位帮主耶律齐得****岳父*****郭靖传授而学全,但此后丐帮历任帮主,因根柢较欠,最多也只学到十四掌为止。

Chinese

Cantonese

欧阳锋始终坚信,

武功在手,天下我有,

而最后,他除了武功,一无所有。

岁月蹉跎,林朝英老了,死了,王重阳回到古墓,

痛哭一场,却依然习惯性的将林朝英的玉女心经破了个干净,

留下特别傻的十六个字:

“玉女心经,技压全真。

重阳一生,不弱于人。”

李若彤(英语:Carman Lee Yeuk Tung;1966年8月16日—),原名李惠娴,香港女演员,主演过《1995神雕侠侣》、《1997天龙八部》、《杨门女将》、《M Club》等多部影视作品,其中她在《神雕侠侣》中所饰演的小龙女一角最广为人知。杨过 ( 古天乐)

《新天龙八部之天山童姥》(英语:The Dragon Chronicles - The Maidens of Heavenly Mountain)是1994年根据金庸武侠小说《天龙八部》改编拍摄而成的武侠电影,由钱永强执导,林青霞、张敏、巩俐主演。

主题曲 《只有我自己》 王菲

金庸大侠的第一部小说是《书剑恩仇录》,此后灵感接踵而来,又一口气创作了

《碧血剑》、

*******《射雕英雄传》、

*******《神雕侠侣》、

《雪山飞狐》、

《飞狐外传》、

*******《倚天屠龙记》、

《连城诀》、

***《天龙八部》、

《侠客行》、

《笑傲江湖》、

《鹿鼎记》、

《越女剑》

等14部小说,一共创作了15部武侠小说,开创了一个崭新的武侠新时代。

《倚天屠龙记》是香港作家金庸所著武侠小说“射雕三部曲”之一。男主角为张无忌,为渠个三部曲个最后一部。作为跨越宋元明三个朝代个武侠传奇故事个结局篇,别样二部包括《射雕英雄传》、《神雕侠侣》是同一个时期(宋末元初)个故事,角色也互相熟识;到《倚天屠龙记》时,已过了快一百年,属于元末明初个故事。

大义心中放, 侠情满胸怀

“你既然是我的过儿,我就跟你一生一世。”

——小龙女对杨过至死不渝的爱情。

“我命由我不由天。”

——杨过对命运抗争、追求自由的精神写照。

四大恶人,善恶谁定?”

——段延庆的反问。

英雄气短,儿女情长。”

——乔峰的矛盾心境。

“天山童姥,容貌虽老,武功盖世。”

——对天山童姥独特魅力的形容。

“名门正派,也不过如此。”

——揭示武林正派虚伪的一面。

我宁可背叛天下人,也不愿天下人背叛我。”

——慕容复对功名的执念。

“你若安好,便是晴天。”

——乔峰对阿朱深沉的爱。

“有情皆孽,无人不冤。”

——揭示了人世间恩怨情仇的本质。

“众生皆苦,唯有自渡。”

——佛理贯穿全书,劝人自我解脱。

“他强由他强,清风拂山岗;他横任他横,明月照大江。”

——虚竹所悟的少林心法,体现无欲无争的心境。

“一切恩怨,终究不过是黄土一抔。”

——对人生无常的深刻体会。

“凡事不可强求,一切随缘自在。”

——《天龙八部》段誉的心境。

“人在江湖,身不由己。”

——《笑傲江湖》令狐冲的无奈。

“有人的地方就有恩怨,有恩怨的地方就是江湖。”

——《笑傲江湖》对江湖的精辟概括。

“侠之大者,为国为民。”

——郭靖的一生写照,也是金庸对侠义精神的高度凝练。

“生亦何欢,死亦何苦。”

——面对生死离别,杨过表现出大彻大悟的洒脱。

亂世英雄,誰與爭鋒!

江湖俠義,鐵漢柔情!

元顺帝至元二年(原著所述之历史空间背景),宋朝覆亡至此已是五十余年。江湖上又为一宝刀争抢。竟是因为一句流传武林已久的箴言

“武林至尊,宝刀屠龙,号令天下,莫敢不从”

及

“倚天不出,谁与争锋”。

再度引得武林再次动荡、腥风血雨。也因为误会中的误会(就像殷素素对张翠山所说的:恩恩怨怨,很难说的清楚...),再度让江湖人士相继赴死。

1273年,元攻克襄陽;郭靖、黃蓉見守城無望,於是請波斯大師熔玄鐵重劍加入異域奇特精金,鑄成了屠龍刀,而倚天劍則無玄鐵成分,是由君子劍與淑女劍所熔。;郭黃隨著城破而亡,郭靖68歲、黃蓉66歲。

金庸“射鵰三部曲”《射鵰英雄傳》《神鵰俠侶》《倚天屠龍記》

《倚天》書中角色有許多為《射鵰》和《神鵰》之故人、後人及傳人。

仗剑天涯平不平,怀情江湖断恩恩

刀出鞘,义薄云天;剑归鞘,恩消泪尽

千山万水行侠道,一剑一琴写红尘

江湖有路人未老,杯酒难忘英雄情

剑光寒,星河万里;酒意暖,故人千觞

一梦江湖风波急,半生肝胆夕阳红

刀光饮血风云暗,剑气凌霄天地清

快马轻舟行侠义,红尘白雪染恩仇

书剑恩仇归梦里,江湖豪情寄天涯

金庸之后,再无江湖

孤身侠客行,千里快哉风。

比如他们的相逢与告别:

这位兄台,请问高姓大名?

青山不改,绿水长流,咱们后会有期。

有人说,1994台版的《倚天屠龙记》,汇聚了史上最媚人的周芷若、最潇洒的杨逍、最豪情的殷天正、最阴险的朱元璋、最讨人厌的丁敏君、还有最迂腐的灭绝师太。

人物个个经典,配乐也是相得益彰。

金庸的江湖世界,有豪气冲天的江湖气,有细腻的儿女柔情,这首《爱江山更爱美人》,李丽芬的独特声线,倒是演绎出了独特的味道。

张无忌与一众女子的缠绵悱恻都置于眼前,江湖道义与儿女情长,自古难以两全。

《刀剑如梦》

台版《倚天屠龙记》播出后,TVB引入版权,并请林夕在片头原曲《刀剑如梦》的基础上,重填粤语歌词《刀剑若梦》,仍由周华健演唱。

国语的《刀剑如梦》和粤语的《刀剑若梦》,两个版本,一字之差,但都高度契合《倚天》中的人物命运。

天龙的主题是:有情皆孽,无人不冤。

《天龙八部》这个名字,即是出自佛家,以“天”及“龙”为首,所以称为“天龙八部”,包含芸芸众生,世相百态。

唐艺昕 建宁公主

杨祺如 双儿 韦小宝老婆之一,山西富商庄允城、庄廷鑨家千金

郭泱 阿 珂 韦小宝老婆之一,为他生下一子,虎头(云骑尉)

朱珠 苏 荃 韦小宝老婆之一,为他生下一子,铜锤,神龙教教主之妻

关芯 沐剑屏 韦小宝老婆之一,沐王府郡主

王伊瑶 方 怡 韦小宝老婆之一,沐剑屏师姐

锺丽丽 曾 柔 韦小宝老婆之一,王屋派弟子

飞雪连天射白鹿, 笑书神侠倚碧鸳

57:10

光明頂教主

Jin Yong, 94, Lionized Author of Chinese Martial Arts Epics, Dies

The novelist Jin Yong in 2002 with his book “Book and Sword, Gratitude and Revenge” at his office in Hong Kong. He was broadly popular with generations of Chinese readers.

Nov. 2, 2018

HONG KONG — Jin Yong, a literary giant of the Chinese-speaking world whose fantastical epic novels inspired countless film, television and video game adaptations and were read by generations of ethnic Chinese, died on Oct. 30 in Hong Kong. He was 94.

His death, at the Hong Kong Sanatorium and Hospital, was confirmed by Ming Pao, the prominent Hong Kong newspaper that Jin Yong helped establish and ran for decades. Chip Tsao, a writer and friend, said the cause of death was organ failure.

Jin Yong, the pen name of Louis Cha, was one of the most widely read 20th-century writers in the Chinese language. The panoramic breadth and depth of the fictional universes he created have been compared to J. R. R. Tolkien’s “The Lord of the Rings” and have been studied as a topic known as “Jinology.”

Jin Yong received his start as a novelist in the mid-1950s while working as a film critic and editor for The New Evening Post in Hong Kong, which was then a British crown colony. He had moved there in 1948 and lived there for most of his life.

From 1955 to 1972, Jin Yong wrote 14 novels and novellas and one short story in the popular genre known as wuxia, which consisted mainly of swashbuckling martial arts adventures.

His first wuxia novel, “The Book and the Sword” (1955), drew its inspiration from a legend that held that the Manchu emperor Qianlong was in fact a Han Chinese who had been switched at birth. The novel was serialized in The New Evening Post and became an instant hit.

By the time he began writing, the Chinese Communist Party had banned wuxia literature, calling it “decadent” and “feudal.” The ban reflected a centuries-old view of wuxia as a marginal genre within the Chinese literary tradition.

But in Hong Kong and other parts of the Chinese diaspora, Jin Yong’s novels helped spearhead a new wave of martial arts fiction in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Image

“Legends of the Condor Heroes 1: A Hero Born,” by Jin Yong.

Jin Yong elevated what had been a rather formulaic genre by blending in poetry, history and fantasy to create hundreds of vivid characters who travel through a mirror underworld that operates according to its own laws and code of ethics.

In tales of love, chivalry, friendship and filial piety, his characters are flawed, with complex emotional histories, making them all the more appealing.

How The Times decides who gets an obituary. There is no formula, scoring system or checklist in determining the news value of a life. We investigate, research and ask around before settling on our subjects. If you know of someone who might be a candidate for a Times obituary, please suggest it here.

Learn more about our process.

“Writing about heroes was very easy,” Jin Yong said in a 2012 interview. “But as I got older I learned that these big heroes actually had another, more contemptible side to them, a side that was not shown to others.”

Translated into many languages, his books have sold tens of millions of copies, fueling a sprawling industry of film, television and video game adaptations.

Jin Yong used martial arts fiction as a vehicle to talk about Chinese history and traditional culture, forging his own fictional vernacular that drew heavily on classical expressions. His stories were often set at pivotal moments in Chinese history, like the rise and fall of dynasties. They made reference to Confucian, Buddhist and Taoist ideas, and positioned martial arts as an integral part of Chinese culture, alongside traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture and calligraphy.

Jin Yong took a “marginal, even disreputable, form of popular fiction and made it both a vehicle for serious literary expression and something that appealed to Chinese readers around the globe,” John Christopher Hamm, an associate professor of Asian languages and literature at the University of Washington, said in a telephone interview.

Following the early success of his novels, Jin Yong established his own newspaper, Ming Pao Daily News, in Hong Kong in 1959. Soon he was publishing installments of his novels while writing daily social commentaries about the horrors of Mao Zedong’s China.

It was a subject he was intimately familiar with: In 1951, his father had been labeled a “class enemy” and was executed by the Communists.

In 1981, as China was beginning to open up economically and politically, Jin Yong traveled to Beijing to meet with Deng Xiaoping, Mao’s successor. Deng confessed that he was an avid fan of Jin Yong’s books.

Not long afterward, China lifted its ban on Jin Yong’s novels. At the time, many young Chinese were eager to read something other than the socialist propaganda they had become accustomed to under Mao.

Notable Deaths 2018: Books

A memorial to those who lost their lives in 2018

“Reading his novels opened our vision,” Liu Jianmei, a professor of contemporary Chinese literature at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, said in a telephone interview. “His way of thinking was so different from what was being cultivated in mainland China at the time.

He helped us think beyond right and wrong, good and bad.”

In 1985, Jin Yong was appointed to a political committee charged with drafting Hong Kong’s Basic Law, the mini-constitution that would govern that semiautonomous city once Britain handed it over, ending colonial rule. He drew criticism for backing a conservative proposal to select the city’s leader without universal suffrage.

Jin Yong’s initial optimism about China’s political opening was dashed by the government’s bloody crackdown on the student-led democracy movement in Tiananmen Square in 1989.

He resigned from the committee in protest. In a tearful interview, he said, “Students’ peaceful petitions should never be suppressed by military force.”

Cha Leung-yung was born the second of seven children on March 10, 1924, in Haining, in the central coastal province of Zhejiang. His father, Zha Shuqing, was an educated landlord. His mother, Xu Lu, was from a wealthy business family.

Jin Yong graduated from Soochow University’s law school in 1948. By then he had begun working as a journalist and translator for the newspaper Ta Kung Pao in Shanghai. In 1948 he moved with the newspaper to Hong Kong, which would become his home for the next seven decades.

He retired from writing novels in 1972. He stepped down as chairman of the Ming Pao Enterprise Corporation in 1993.

Jin Yong is survived by his third wife, Lam Lok Yi, and his children from his second marriage: a son, Andrew, and two daughters, Grace and Edna.

This year, the first installment of Jin Yong’s popular trilogy, “Legends of the Condor Heroes,” was translated into English, by Anna Holmwood.

Among readers of original Chinese versions, Jin Yong had no shortage of prominent fans. They include Jack Ma, the chairman of Alibaba, who at one point gave employees nicknames drawn from characters in the novels.

This post has been edited by plouffle0789: May 30 2025, 09:11 PM

Jan 7 2025, 11:59 PM, updated 6 months ago

Jan 7 2025, 11:59 PM, updated 6 months ago

Quote

Quote

0.0254sec

0.0254sec

0.41

0.41

5 queries

5 queries

GZIP Disabled

GZIP Disabled