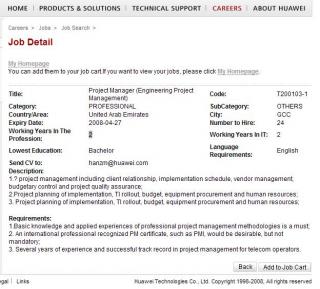

|

In just 18 years, Huawei has grown from a corporate midget into a mighty global contender in one of the world's key industries. In 1988, when the Chinese company was founded by Ren Zhengfei, a former People's Liberation Army officer and a current Communist Party member, it essentially resold imported telecom gear for the domestic market. Nobody outside China paid much attention to the firm. Today, everybody does--and not only for commercial reasons. Huawei has become a major manufacturer of wireless phone and networking equipment, with offices in 41 countries. The company competes with multinational big boys--Northern Telecom, Alcatel, Lucent, Cisco Systems--and wins business from the world's top network operating companies, mostly by significantly undercutting the prices of its competitors in the equipment business. Huawei's sales jumped to more than $4 billion in the first half of 2005, 85 percent higher than the same period a year before, and more than half its orders (by value) come from markets outside China.

So why do some Western politicians and business executives furrow their brows when Huawei comes calling? Perhaps because Huawei, like many fast-growing Chinese companies, is a little too close to the Chinese government, and a little too obsessed with acquiring advanced technology. While Huawei already has an R&D operation in India, for instance, the Foreign Investment Promotion Board has been sitting on its application for a $60 million expansion in Bangalore to develop software for its equipment for months. At the same time, Huawei has applied for a license to bid as an equipment supplier for large-scale Indian telecom projects run by state-owned service providers MTNL and BSNL. But the Telecom Ministry, likewise, has blocked that application. According to press reports, India's Intelligence Bureau suspects that Huawei has ties to China's intelligence apparatus and military, and even performs the debugging sweeps for the Chinese Embassy in India. (Huawei says that's not true.)

Political conservatives in Britain expressed the same security concerns about Huawei last spring. In April, the company won a $140 million contract to build part of British Telecom's "21st Century Network," a major overhaul of its equipment. But when rumors began circulating that the Chinese company might then bid on Marconi, a landmark electronics and information technology firm that was being put up for sale, a Conservative Party spokesman sounded the alarm. The Tories asked the British government to consider the implications for Britain's defense industry of a Chinese takeover of Marconi. In the end, Huawei didn't make an offer, and the Swedish telecom giant Ericsson is in the process of buying Marconi.

Like China National Offshore Oil Corporation, Lenovo, Haier and other Chinese corporate juggernauts, it's hard to know quite what to make of Huawei. Is it a security menace bent on doing Beijing's bidding, a legitimate international telecom competitor, or a corporate house of cards, all market share and PR releases but no profits? It's hard to answer those questions. CEO Ren refuses to talk with journalists, and there are persistent rumors that the firm is actually run by the People's Liberation Army. The company denies that, and has long claimed it no longer has any ties to the government. Huawei's books are audited by a well-known accounting firm (KPMG), but few of its financial numbers are made public. Opaque bookkeeping has also frightened analysts: an August report by the Thailand-based consulting company MWL argues that Huawei may rely on "unsustainably low prices and government export assistance" to make sales. The report adds that some customers "should be wary of making it a primary supplier for now."

Huawei has also been dogged by accusations of intellectual-property theft and corporate espionage. In 2003, Cisco sued the company in a U.S. court for copying computer codes used in its routers, machines that connect online networks. According to court documents, Huawei even copied Cisco's model numbers to make it easier for customers to switch to cheaper Huawei versions. Cisco eventually dropped the suit--but only after Huawei pulled the contested products from the market and agreed to alter their design codes. Neither company will reveal other details about the settlement.

The story of Huawei's rise--from its murky finances and purported government links to its rapid move into global markets thanks to bargain-basement prices--is a window on the aspirations and operations of China Inc. Many Chinese companies are beginning to compete in the global market with Western heavyweights, raising the questions: do they really have the innovative instincts and management expertise to become legitimate multinationals, and is Beijing now more a help or a hindrance to their ambitions? In April, the computer maker Lenovo, which is partly owned by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the country's top research body, signed a $1.75 billion deal to buy IBM's personal-computer manufacturing unit. Two months later the Chinese oil company Cnooc, 70 percent of which is owned by the state, bid $18.5 billion to acquire the American firm Unocal. Fears that U.S. politicians would block the deal and a higher bid by Chevron forced Cnooc to pull out. Still, analysts say, the trend is clear: as the domestic Chinese market becomes more competitive, major Chinese firms are determined to become global players, whatever the cost.

|

Most of us went for walk-in is tech support, some able to get Microwave planning engineer. This is the coolest job in the company i think, most professional job if compare to others. Most of the engineer is in tech support post.

Most of us went for walk-in is tech support, some able to get Microwave planning engineer. This is the coolest job in the company i think, most professional job if compare to others. Most of the engineer is in tech support post.

May 13 2008, 09:52 PM

May 13 2008, 09:52 PM

Quote

Quote

0.0270sec

0.0270sec

0.52

0.52

6 queries

6 queries

GZIP Disabled

GZIP Disabled